The Popstar as Brand: Rihanna and the Luxury of Not Caring

How Rihanna turned public tragedy into private power.

i. opening: the myth of rihanna

Oh, Rihanna.

The woman, the myth, the alternative popstar legend.

Rihanna gave us some of the greatest singles of the 2010s, but her story is one wrapped in an undercurrent of tragedy. When you become one of the most consumed women on the planet, the line between survival and self-reinvention gets blurry.

You probably read the title and thought, “Hm. She’s definitely about to talk about Fenty, the billionaire arc, and her seven-year musical disappearing act.”

But I’m not starting there. I’m zeroing in on 2009–2012 — the era where Rihanna didn’t just evolve; she had to save her own brand from public annihilation.

This was the period where she learned the choreography of “not caring.” Not because she naturally embodied that energy, but because the alternative — vulnerability, softness, public grief — would have gotten her crucified.

In those years, Rihanna wasn’t crafting a persona. She was performing emotional armor. She was building a version of herself the world couldn’t destroy so easily.

ii. 2009: the cultural violence of the chris brown incident

I was nine when I first saw those photos. Nine years old when I quietly learned that the world will always disrespect the Black woman.

The idea of going to the police in your darkest moment and having someone sell those photos to a tabloid. Turning your pain into content for a quick buck. It still sickens me.

It’s one thing to get your face beaten. It’s another to have the entire world pass it around like a spectacle. Yes, there was outrage when the images leaked — but the damage was already done. Her most private, horrifying moment was immediately absorbed into the entertainment cycle.

The official court documents describe the assault in detail. He beat her with his fists for roughly thirty minutes as he attempted to drive their rented car. For years, people tried to debate the “truth” of what happened — she kicked him, he claimed she spit on him — but the actual record states she kicked him only in an attempt to get away after he punched her repeatedly and put her in a headlock.

The public, of course, was ruthless.

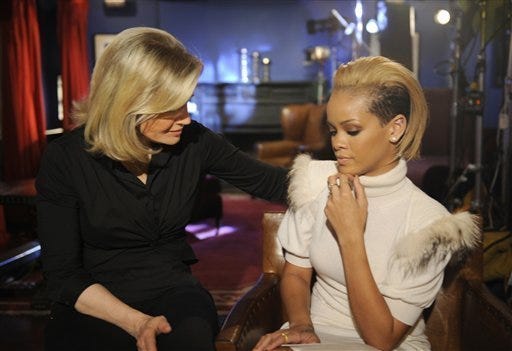

Abuse victims are always trapped between a rock and a hard place. Both Rihanna and Brown went on their own image-rehabilitation tours, but Rihanna’s ABC interview with Diane Sawyer remains one of the most heartbreaking moments of her career.

Sawyer interrogates her, demanding to know why she went back, demanding she “explain herself” to young girls. The subtext is unmistakable:

justify your pain, or we will blame you for it.

How dare Diane Sawyer place the burden of abuse on the victim?

The public wanted a perfect victim. They still do.

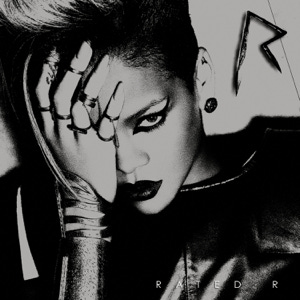

iii. rated r and the reinvention of a survivor

Revisiting Rated R with this added context is upsetting.

Russian Roulette is an obvious nod to an abusive relationship. Hard is a young woman letting the world know they can’t break her. How heartbreaking is that? This young woman needed comfort but couldn’t receive it — because it would likely cost her career.

Rated R was recorded in March of 2009, mere weeks after the incident. Ne-Yo and Justin Timberlake helped her write a few songs. Speaking about the album, Ne-Yo told MTV:

“Rihanna is not in the same place mentally. She’s more comfortable in her skin now... it’s refreshing to watch.”

Ah yes. She’s assaulted, publicly humiliated, and forced to rebuild her entire persona — and the takeaway is that she’s “comfortable in her skin.”

In 2009, a survey of 200 teenagers in Boston found that 46% believed Rihanna was responsible for the violence inflicted on her. 52% believed “both parties” should be held accountable.

Notice how it’s never the man’s fault?

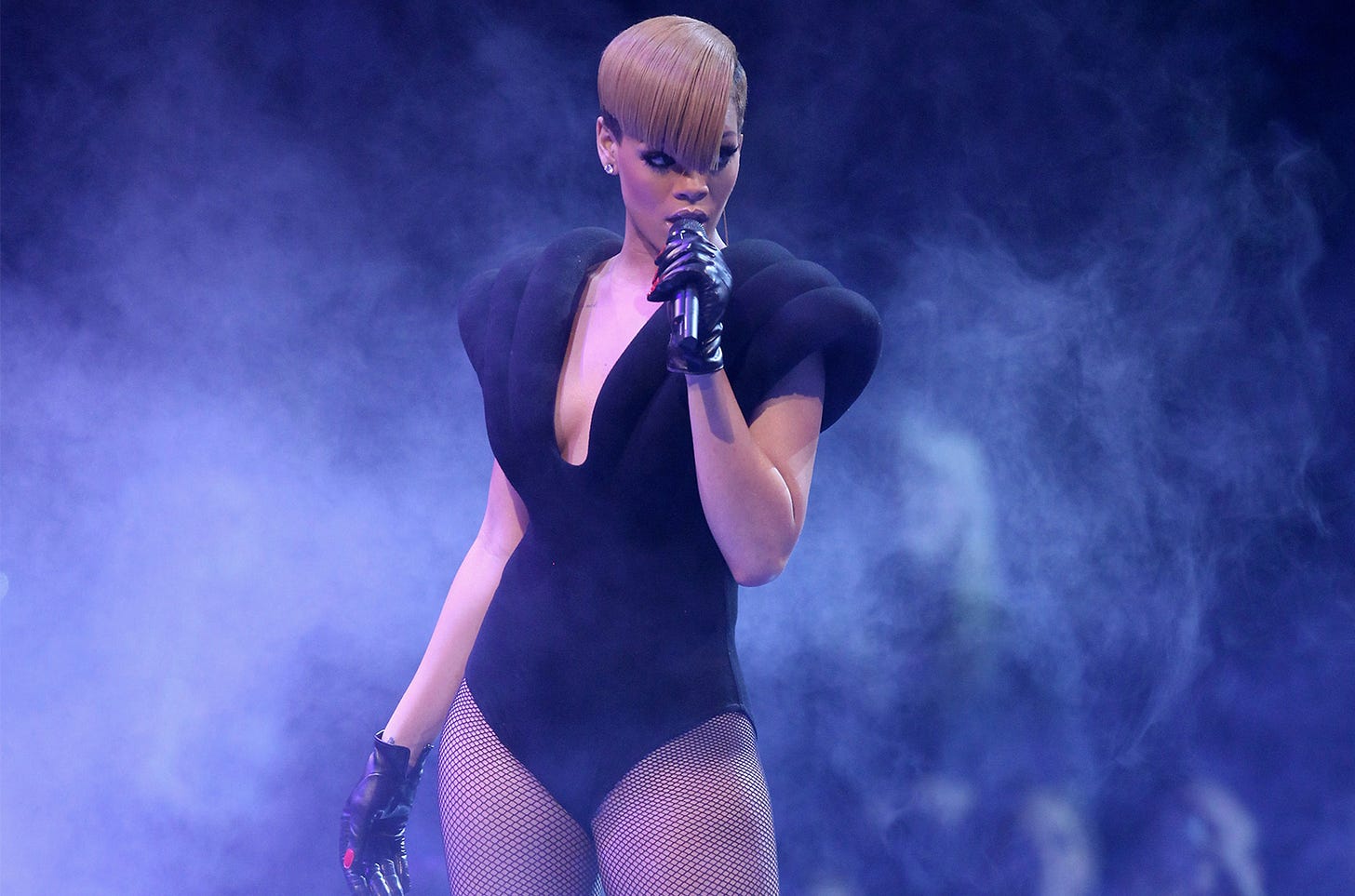

What makes all of this even more tragic is that Rihanna’s response — the hardness, the unbothered attitude, the bad-bitch armor — became the very thing the public celebrated her for. But that persona wasn’t rebellion. It was survival.

When the world decides you’re not the perfect victim, the only acceptable option is to be strong, silent, and untouchable.

Rihanna didn’t set out to embody the stereotype forced onto Black women. She was trying to protect herself from a culture that refused to see her humanity.

And the worst part? The more she performed strength, the more people pretended it was natural to her — as if she hadn’t been pushed into it.

As a recurring theme of this series, I’m trying to articulate how we force women in the spotlight to perform sexuality in order to signify maturity. Britney was sacrificed for doing it too early. Miley appropriated Black culture to make it palatable. Taylor Swift refuses to make the transition at all.

Maybe Rihanna would’ve reached Rated R on her own. She began exploring edgier music with Good Girl Gone Bad two years prior. But it’s no coincidence that this album was written weeks after the assault.

She had something to say.

And maybe the world wasn’t really listening.

iv. the machine keeps moving: jive records and industry complicity

In Toxic: Women, Fame, and the Tabloid 2000s, Sarah Ditum never outright names a villain. She doesn’t need to. Instead, she traces patterns — quietly, carefully — and allows the reader to sit with what keeps repeating.

One name keeps resurfacing (for myself as I write and research for these essays, anyway).

Jive Records.

And guess who was signed to the label?

Aaliyah and R. Kelly.

Britney Spears and Justin Timberlake.

Chris Brown.

Ditum doesn’t argue that Jive orchestrated abuse. What she implies is more unsettling than that: the label repeatedly positioned young women inside power dynamics that benefited male collaborators, romantic partners, or cultural foils — and then stepped back when those dynamics curdled into harm.

These women weren’t protected as people. They were managed as assets.

The relationships were branded as chemistry. Synergy. Storyline. When they produced hits, they were celebrated. When they produced damage, responsibility disappeared. No one person was at fault. No one intervened. The machine kept moving.

Because the industry’s real priority isn’t safety. It’s continuity.

Albums must be released. Tours must go on. Narratives must stay on track.

Grief is inconvenient. Trauma is disruptive. Abuse is only a problem when it interrupts profit.

And we have proof. Jive Records knew about R. Kelly’s behavior — at least by the late ’90s — and did nothing to stop it. He stayed with the label until 2011, when they were absorbed into RCA.

In 2018, the Washington Post published an article stating that executives at Jive were aware of Kelly’s actions for years but didn’t intervene because of how much money he was making the label. Larry Khan and Barry Weiss — both former Jive execs — even said on the record that his personal life wasn’t their responsibility.

So, is it really that absurd to assume Jive didn’t care about Chris Brown beating Rihanna?

Or about Justin Timberlake’s public humiliation ritual of Britney Spears? Janet Jackson?

R. Kelly earned Jive hundreds of millions of dollars over the years.

Britney did too — especially after being vilified in Cry Me a River, a music video that gave the public permission to treat her like a joke for the next twenty years.

And that makes Rihanna’s options pretty clear.

She could be the battered, empowered survivor. Or she could become irrelevant.

A punchline. A warning. Another cautionary tale like Britney.

When there’s no one willing to defend you — not your label, not the press, not even your own sex (Diane Sawyer, I’m looking at you) — what would you choose?

v. performance, pain, and the “perfect victim”

In that context, Rihanna’s experience begins to look less like a singular tragedy and more like a familiar outcome.

Once again, a young woman absorbs the fallout. Once again, the man’s career survives. Once again, the public asks her to be strong about it.

Once again, we ignore the functional reality of millions of victims. It’s proven that it takes seven tries to leave your abuser. Rihanna was in an on-and-off relationship with Brown until 2012.

Brown’s behavior wasn’t a one-off either. There are dozens of reports of violence perpetrated by Brown and main of those reports involve women.

Rihanna was a young woman that needed some form of guidance but received public scrutiny instead. She was antagonized by Diane Sawyer on national television, photos of her battered face were released for public consumption, and the common opinion is that she deserved it.

Rather than accept facts presented to us as they are, culturally, we prefer to jump through hoops to dismiss them.

The concept of the “perfect victim” is a sad one.

For your trauma to be justified, it must be horrific and violent. You must barely survive it and walk away with noticeable bodily injury. It must completely and visibly alter your individual state. It must change you permanently for the rest of your life. When the world looks at you, they must see a victim. Not a survivor.

Just ask Amber Heard.

During the Depp vs Heard trial, the conversations that were happening online were abhorrent. To watch someone be forced to testify in a case she technically already won in the U.K. and to have it aired live every single day — is dehumanizing.

Every tear, runny nose, readjustment, huff, eye rub was screenshotted and turned into a meme. Youtubers and podcasters made MILLIONS dissecting and disrespecting Amber Heard.

The photo evidence wasn’t enough. Previous testimony wasn’t enough. Her becoming emotional on the stand wasn’t enough.

In the minds of millions, especially women, she was a liar. A fake. A gold digger. She was a manipulative femme fatale that chose Depp as her victim. She wanted his money, his fame, his life. His alcoholism and drug use was all her fault. Despite dozens of reports that Hollywood was growing tired of Depp and his washed-up actor shenanigans, another beautiful woman was left hung out to dry.

And here’s the wildest part: the public eventually forgave Chris Brown.

He released hit singles, won awards, collaborated with every major artist. And in response? Rihanna forgave him too. Not for him — maybe for herself. Maybe for the sake of control. She knew the world wouldn’t let her linger in pain. So she got to work.

Between 2009 and 2012, she released four albums in three years.

She gave them bangers. She gave them fashion. She gave them “Unapologetic.” She tried to make them forget she was ever a victim. To see her as Rihanna again.

But the question is — did it work?

Or did she just become something else — a version of herself the world could stomach?

vi. the price of surviving

This is the trap.

If you’re not likable, no one believes you. If you’re not silent, you’re manipulative. If you’re not inspirational, you’re damaged. If you stay, you’re an idiot. If you leave, you’re a liar. If you cry, you’re hysterical. If you don’t, you must not be telling the truth.

We’ve made it impossible for victims to exist. So instead, we give them two options: disappear quietly or survive loudly enough to entertain us.

And Rihanna chose survival.

She left the music industry behind and ascended. Now she’s a businesswoman among the echelons of Beyonce and Jay-Z.

She appears publicly but never long enough to be consumed. And as the years pass and the people that exist online get younger, 2009 becomes a distant memory.

Untouchable. Powerful. Sexy. Unbothered. She walked away from the industry that consumed her and re-emerged on her own terms — as a billionaire, a mother, a mogul. A woman who said: you don’t get to watch me suffer anymore.

Not because the pain vanished. But because she finally had the power to protect herself from it.

That’s the triumph.

She didn’t just survive what the world did to her — she built something lasting out of it. And in doing so, she showed other women what’s possible when you stop asking for permission to heal.

Rihanna didn’t just become a brand. She became a boundary. She drew a line and said: this far, no further.

She became a blueprint.

And this time, the cost wasn’t her.

this is literally my favorite series ever. keep writing these PLEASE

first. can’t wait to read this!!!