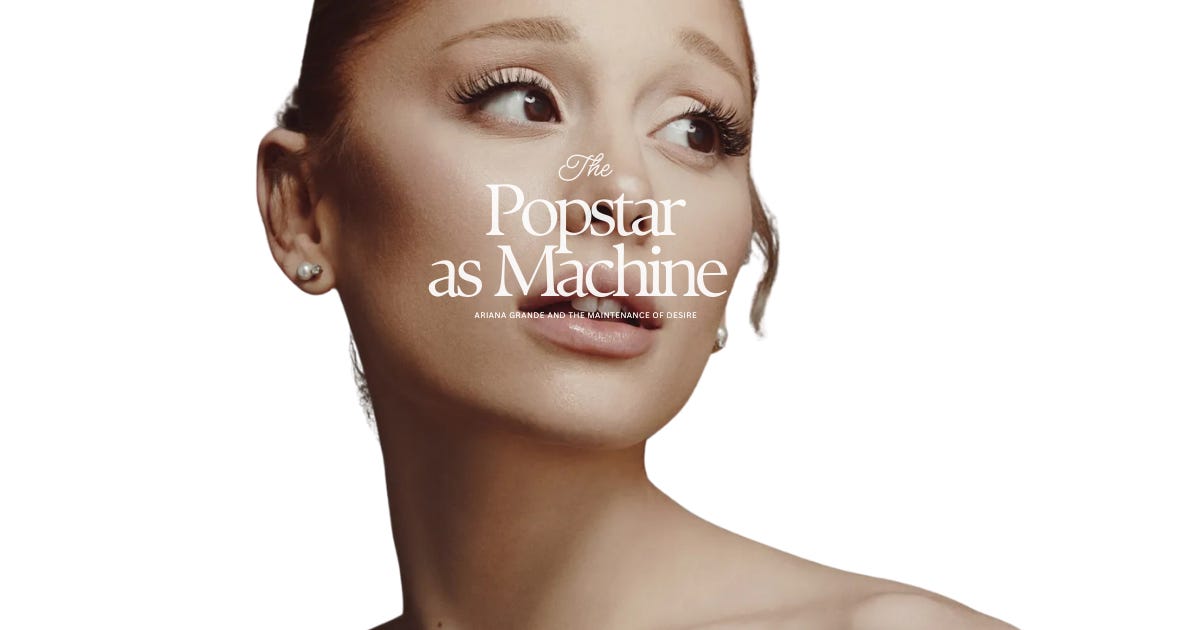

The Popstar as Machine: Ariana Grande and the Maintenance of Desire

On Discipline, Desire, and the Cost of Staying Intact

i. introduction

Truthfully, I was more of a Disney Channel girl than a Nickelodeon girl.

This was likely because my mother never wanted to pay Comcast extra so I could actually watch Nickelodeon — but that’s okay, I’ve gotten over it.

Drake Bell was my first crush. Beck from Victorious was my second (Avan Jogia, if you ever read this, I love you — tell Halsey I said hello). Naturally, I stopped watching Nickelodeon when Victorious was canceled, because I refused to watch The Thundermans.

The fascinating thing about being a child star is that not everyone survives the process. You are either mediocre — good enough and promptly forgotten — or excellent and punished for it through prolonged public humiliation.

Disney was simply better at the machine of child stardom. Record deals through their own label. Branded merchandise with your face in every mall in America. Television crossovers, DCOM cameos, morning show appearances. They did not play games with their talent.

If you wanted to be famous, you were going to work.

Disney Channel made stars. Nickelodeon did not. Trust me — they tried.

Miranda Cosgrove.

Jeanette McCurdy.

Victoria Justice.

Jamie Lynn Spears.

No one was rushing out to buy their latest record.

Nickelodeon, by contrast, was messier. Louder. Less polished. Its stars weren’t trained to scale — they were exaggerated, caricatured, and discarded once the joke wore thin. Which is why Ariana Grande never looked like a survivor of that system.

She looked like an accident.

Which is what made her so efficient.

ii. cat valentine and the safety of infantilization

Much of my writing is framed through the lens of a child who lived through these moments. To me, Ariana Grande was Cat Valentine — and for years, I didn’t understand why people cared so much about Cat from Victorious at all.

Even now, in her early thirties, Grande has never fully shaken the ditzy redhead image Nickelodeon stamped onto her. Her early brand existed as a kind of kaleidoscope: baby-faced ingénue, cartoonish femininity, and a Mariah Carey–esque voice that felt almost incongruent with her presentation.

The high ponytail. Puffy skirts. Crop tops and tights. She stood with one foot still wedged firmly in the Nickelodeon door and the other hovering just shy of legitimate pop stardom.

Her sexual appeal wasn’t threatening — because, in a sense, it didn’t really exist yet. There was no urgent need for handlers to panic over a chaotic Britney Spears– or Rihanna-level implosion. The public didn’t perceive her as volatile, dangerous, or even particularly adult.

She wasn’t a scandal waiting to happen. She was safe.

Her appeal, at the time, was closer to Christina Aguilera in theory — vocal talent first — but without the aggression, hunger, or visible rebellion. Grande’s image didn’t ask to be taken seriously.

To this day, the most persistent criticisms surrounding Grande are almost entirely about her body. In her early twenties, she was “too small,” “too thin,” “too childlike.”

As body image conversations shift toward neutrality and acceptance, Grande’s body continues to surface in online forums, dissected with an almost clinical familiarity. Rather than entertaining the possibility of chronic illness, stress, or lifelong struggle, the discourse defaults to blame. Control must be intentional. Discipline must be rewarded or punished.

What’s striking is not that her body remains a topic of conversation, but that the conversation never evolves. There is no scandal attached to it. Her body is not a site of rebellion or refusal — it is proof of maintenance.

And this is where the machine becomes visible.

Grande’s image is curated so meticulously that even transgression feels inert. Her romantic scandals register as background noise. There is no fall from grace because there is no grace to fall from — only consistency.

This is the paradox of Ariana Grande: her image management is so effective that it renders her almost boring and nonthreatening. Beyond her undeniable vocal talent, there is very little left to interrogate — because every potential point of intrigue has already been neutralized.

iii. the body as proof of discipline

The structure of any body-based mental illness — and any body-based performance — hinges on the idea of discipline. Maintenance requires consistency. Visibility requires control. To successfully sustain a body under constant public scrutiny is to signal obedience to routine, restraint, and labor.

A pop star is nothing if not disciplined. Rehearsals. Appearances. Paparazzi shots. Photoshoots. Meet-and-greets. Brand deals. Acting pursuits. Every output is another moving part in the machine of legibility. To show up repeatedly, polished and precise, is a form of work not everyone survives. Many break under it. Others disappear.

In 2013, Ariana Grande was labeled “too thin” — not because of widespread concern for her health, but because men no longer found her body desirable.

Strike one in the pop star playbook. If men don’t want you, you can’t sell fantasy to that market.

In 2025, she is thinner still, and the tone has shifted to outrage. Not care, exactly — but condemnation. Having an eating disorder is no longer culturally transgressive or romanticized the way it once was. Now, thinness reads as irresponsibility. The pop star turned actress becomes a threat to public health rather than an object of desire.

Women on the internet have spent the last several years dissecting Grande’s appearance with a fixation that feels less like concern and more like surveillance. The tone resembles that moment in a zombie movie when someone in the group has been bitten — and everyone knows it — but no one says anything outright. Instead, they watch and wait for proof.

The body becomes evidence. A future collapse is imagined, rehearsed, and almost desired. Not because the audience wants harm, but because pop culture is conditioned to expect consequence. A visible breaking point would confirm that the machine has limits.

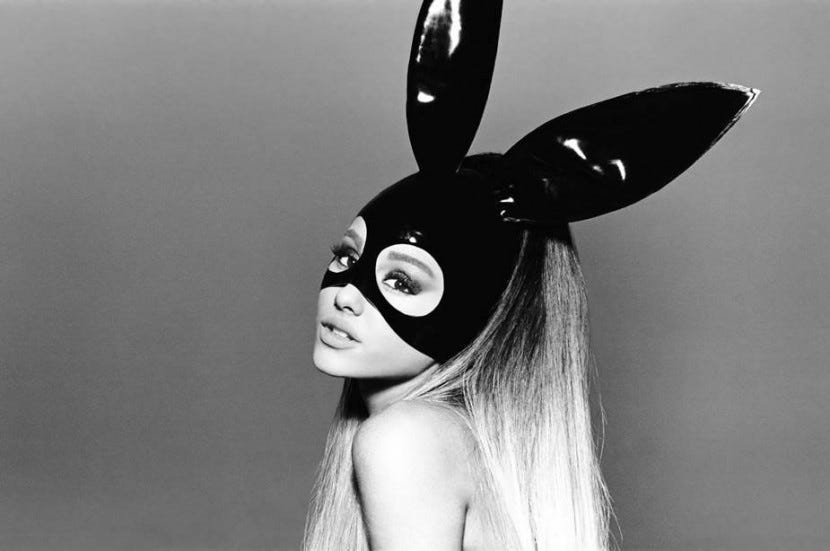

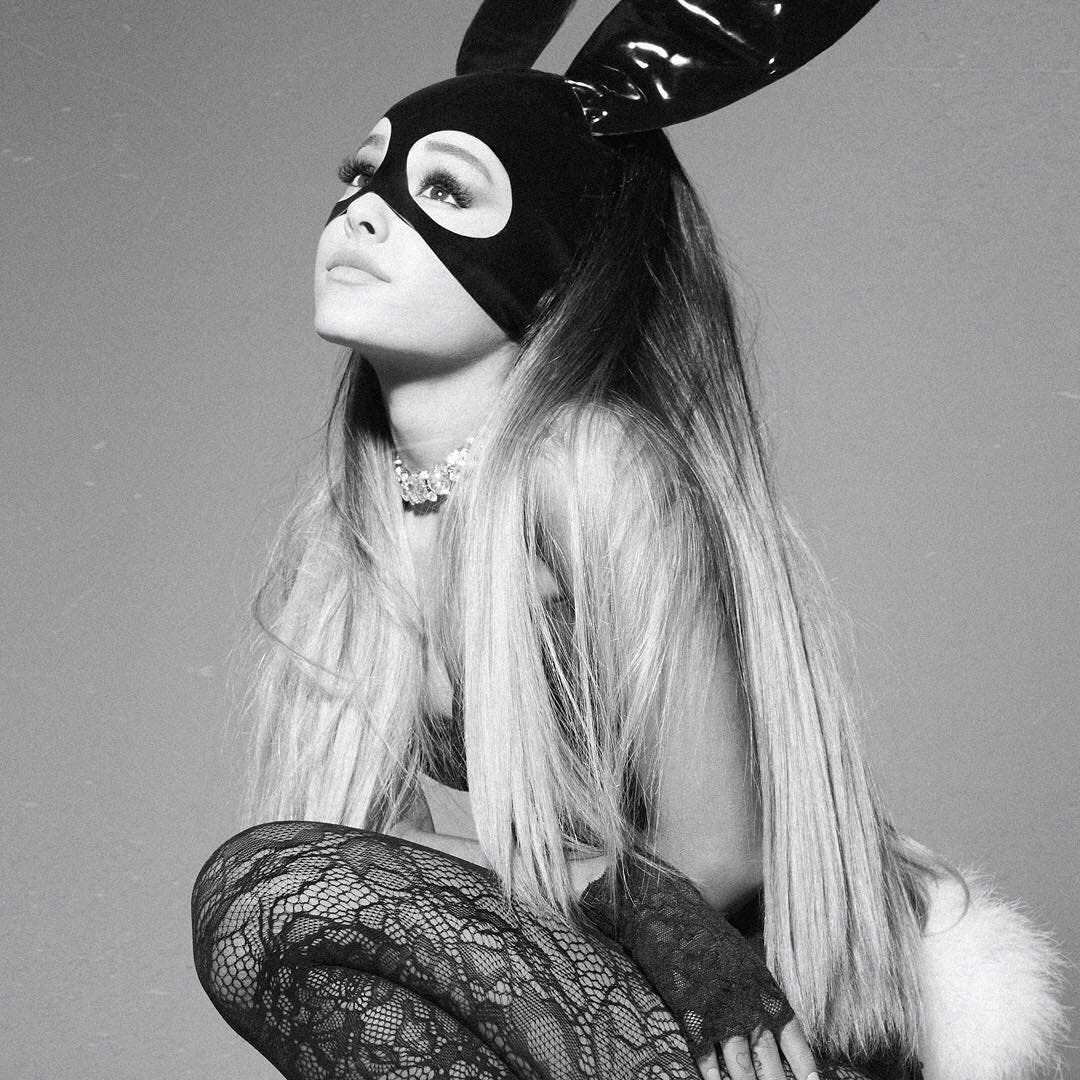

iv. dangerous woman as a reframe

When Dangerous Woman was released in 2016, many critics noted its lack of cohesion. Caitlin White, writing for BKMAG, observed that it was “rather ironic” the lead single was titled Focus, because that’s exactly what the record lacked. The critique wasn’t about Grande’s ability — her voice was, as always, unimpeachable — but about credibility.

Quinn Moreland’s Pitchfork review pushed this idea further. Grande was praised for her technical skill but faulted for emotional distance. She remained guarded, withholding, difficult to access. What was meant to be a sexual pivot felt strangely safe — not because of prudishness, but because nothing about the album threatened her existing image.

This was not a rebellion. It was a resize.

The latex bunny ears, the monochrome visuals, the sultry production — all of it signaled adulthood without risk. Sexuality was introduced as aesthetic, not behavior. There was no public unraveling, no tabloid spiral, no visible loss of control to accompany the shift. Desire was presented carefully, as something to be looked at rather than lived through.

Critics struggled to believe the persona because belief requires exposure. Dangerous Woman asks the listener to accept intimacy without ever offering vulnerability. The album flirts with R&B — a genre that depends on emotional proximity — yet Grande keeps herself at a deliberate remove. The songs are technically excellent, often thrilling in isolation, but resistant to confession.

At the time of Dangerous Woman, Grande was still in transition: no longer Cat Valentine, not yet a figure capable of rupture. The album does not mark a break in her career, but a test of its elasticity. How much adulthood could be layered onto her image without destabilizing it?

The answer, it turns out, was quite a lot — as long as nothing actually changed.

Ariana was often viewed as a kind of Barbie doll — talented and pretty enough, styled in girlish outfits, but curiously hollow beneath the surface. She sings about sex with a sense of remove, marked by a limitation of lived experience rather than transgression.

Her albums are tonally fractured — oscillating between innocence and sensuality — yet consistently yield excellent singles. Grande is a master of surface-level precision, even when the interior world remains carefully sealed off.

Her voice performs exceptionally well under R&B instruction — Sweetener received an 8 from Pitchfork, after all — but R&B as a genre demands a certain intimacy, a willingness to be emotionally legible. The result is music that is technically impressive, often beautiful, but deliberately withholding.

v. desire without scandal

This is likely why her image registers as boring.

Even as fans spend years piecing together her relationship timelines and labeling her a homewrecker, no one ever really cares. It mostly lives online as a running joke. People would rather circle the conversation back to her body, or to the fact that they think Ethan Slater is ugly.

The narrative never sticks.

In an era of Notes app apologies, Ariana simply never acknowledges it. She and Ethan are rarely photographed together. She’s never publicly discussed him in any way that reads as romantic or intimate.

She doesn’t perform shame. She doesn’t engage in public self-flagellation. And without those things, the punishment never arrives.

Instead, she increases her output.

The brand of Ariana Grande is never interrupted. The machine keeps chugging along. If she existed fifteen years earlier, her face would have been plastered across every OK! magazine in the checkout aisle. She would have sat for a Good Morning America interview. There would have been a Diane Sawyer special.

Now, output rinses tabloid fodder out of the news cycle.

Singer transitions into beloved, Oscar-nominated actress.

R.E.M. Beauty.

Wicked.

Eternal Sunshine.

A world tour.

Two things she once swore she had no plans to do anytime soon. She made it clear — this tour is a last hurrah for what we understand to be the Ariana Grande brand.

In 2024, she appeared on The Zack Sang Show and said she had no intention of releasing an album during Wicked. She claimed the 2023 Writers’ Strike simply left her with extra time, and she “decided” to record new music.

Coincidentally, that was also the year news of her relationship with a married Ethan Slater broke.

Was her album Eternal Sunshine image control? What is there to criticize if Grande consistently and successfully proves her cultural value?

vi. outro

Ariana Grande didn’t escape the system that consumes women in pop culture. She learned how to survive it by never giving it what it wants most.

Sexuality, for women, only matters when it devastates you. Desire is only legible when it collapses your interior world. Tragedy only registers when it derails the machine entirely. Grande never lets it get that far.

Her body is maintained, not sacrificed. Her relationships are absorbed, not punished. Her sexuality is staged rather than lived through in public. Every potential rupture is redirected into output, and the machine keeps moving quietly and efficiently.

Ariana Grande remains intact because she never allows herself to become narratively interesting in the way pop culture demands of women. She has been able to do what Taylor Swift cannot. She has ruled her career with an iron fist that has transitioned her from good girl into an adult woman. She’ll get that Oscar one day and she’ll have rightfully earned it.

The pop machine didn’t break her.

It made her sustainable.

this series is so interesting! I can't wait to read the rest of them!